The Jean Charles band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw have lived in the same place for more than 200 years.

The tribe's oral history has it that a Frenchman named Jean Marie Naquin married a Native American woman named Pauline Verdin in the early 1800s — and that Mr. Naquin's parents didn't take too kindly to their child's mixed marriage.

\n\nThe couple fled this familial wrath and settled on Isle de Jean Charles, a narrow inlet in the Louisiana bayou near Terrebonne Parish, about 11 miles off the mainland. The couple was soon joined by several other Native American families and this small community of indigenous Cajuns has lived there ever since...

A thatched roof island home on Isle de Jean Charles. Photo from NARA/New Deal Network/Library of Congress.

until now...

By the middle of the 20th century, there were nearly 400 people living on the island. At that point, the land was 11 miles long and five miles wide — providing this Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribe with 55 square miles of lush, open land on which to hunt, farm, and thrive.

\n\nBut all that's left today is a half square mile of marshland — two miles long and a quarter-mile wide — with two dozen families struggling to survive.

Isle de Jean Charles in 2007, after Hurricane Gustave. Photo by Karen Gadbois/Flickr.

Over the last half-century, rising water levels and increasingly frequent natural disasters have all but destroyed the Louisiana shoreline.

"I'm not going to keep doing this," said Chief Albert Naquin in 2008. Naquin is a direct descendent of the island's first settlers, who inherited the title from his brother in 1997.

\n\nBut Naquin himself doesn't even live on the island anymore. He packed up and moved across the bayou in the 1970s, in an effort to keep his job on the mainland — because the only road off the island was quickly disappearing. The chief had hoped that the rest of his tribe would follow, but 40 years later, some 25 families still remain.

\n\n\n\n\n\n\n\n\n\n"At one time I didn't want to relocate — I thought it would be like another Trail of Tears," he told the Washington Post in 2009. "But now I see that is a selfish viewpoint. It's only a matter of time before the island's gone — one more good hurricane, and we'll be wiped out."

Albert Naquin's parents, Mr. and Mrs. Victor Naquin. Photo by NARA/New Deal Network/Library of Congress.

But the families who still live there don't want to lose that ancestral connection to the island.

"All of our history, all of our ancestral line — that's where our people are buried. That's where our family members were born,"said Chantel Coverdelle, the community's tribal secretary. "They were raised there, and they raised their kids and grandkids. We've been there forever."

\n\nThe island's remaining residents still speak their own colloquial French-Cajun dialect and work as fishermen, oystermen, and fur trappers to survive. But ecological damage has made that work hard to come by too.

Photo by Karen Gadbois/Flickr.

"People used to grow everything themselves; now you have to buy canned beans," a member of the tribe explained to the Washington Post. "People used to have cattle, but now you don't because you don't have any place to put them. We used to do for ourselves; now we have to rely on stores, and that means we have to get different jobs. It used to be everyone would share; now that's not around anymore. It just kills me."

"Island Road," the only landbridge between the island and the mainland, which was built in 1953 and still floods during storms. Screenshot from "Can't Stop the Water"/Vimeo.

Not to mention the island's last schoolhouse, a tiny one-room structure, closed nearly 50 years ago. This has created a devastating cycle of poverty and undereducation for those who remain on the island.

While it might be too late to save Isle de Jean Charles itself, it's not too late to save the tribe — thanks to a $48 million grant from the U.S. government.

Dardar is illiterate, so his son made this sign for him. Screenshot from "Can't Stop the Water"/Vimeo.

This last-minute financial savior comes as part of a National Disaster Resilience competition through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, which is providing more than $1 billion in funding for American communities that have suffered from natural disasters — making the Jean Charles band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw the first official U.S. refugees from climate change.

\n\n\n\n\n\n\n\n\n\n\n\n"I’m very, very excited. I’ve been working on this for 13 years," Chief Naquin told Indian Country Today.

\n\n\n\n\n\n"Now we’re getting a chance to reunite the family. They’re excited as well. Our culture is going to stay intact, [but] we’ve got to get the interest back in our youth."

It's nice to finally see the U.S. government taking action to protect Native Americans. Let's just hope it happens again.

Climate change isn't going away. In fact, it's only getting worse from here on out.

\n\nAnd while we can't undo the mass eradication of Native American people, it's not too late for us to help the ones left — especially since towns like Kivalina and Shishmaref have already spent years dealing with the brunt of our worsening planetary disaster.

\n\n\n\n\n\n\n\nAt the rate we're going, cultural preservation is the only hope we have. But if we work together, maybe that's enough.

\n\n\n\n\n\n\n\nHere's the trailer for a documentary film about the tribe on Isle de Jean Charles:

Patagona has always done a great job taking care of its employeesYukiko Matsuoka/Flickr

Patagona has always done a great job taking care of its employeesYukiko Matsuoka/Flickr While nursing my baby during a morning meeting the other day after a…

While nursing my baby during a morning meeting the other day after a… Not sure if Dwight Schrute would be as accomodating.

Not sure if Dwight Schrute would be as accomodating. This is a teacher who cares.

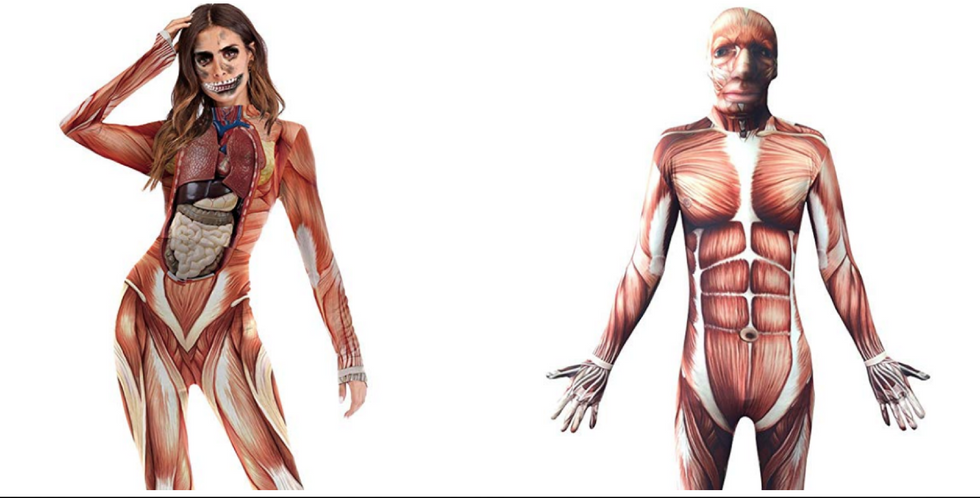

This is a teacher who cares.  Halloween costume, check.

Halloween costume, check.  "The conditions had turned WHAT?"

"The conditions had turned WHAT?" John Calhoun poses with his rodents inside the mouse utopia.Yoichi R Okamoto, Public Domain

John Calhoun poses with his rodents inside the mouse utopia.Yoichi R Okamoto, Public Domain Alpha male mice, anyone?

Photo by

Alpha male mice, anyone?

Photo by