In 1972, he was put in solitary confinement. He's been there since, but now there's hope.

If the goal is to bring an end to solitary confinement, this is a big step in the right direction.

For more than 40 years, Albert Woodfox has lived in solitary confinement at Louisiana State Penitentiary.

Originally convicted along with two others of armed robbery in 1971, Woodfox — who is now 68 years old — would later be accused and convicted of murdering one of the prison's guards.

After receiving a new sentence of life in prison, Woodfox was moved into solitary confinement, where he spent the next 43 years. In June of last year, an appeals court ordered Woodfox released from prison, citing a lack of evidence, only to have that decision reversed. In November, a federal appeals court ruled that Woodfox could be made to stand trial for a third time; his first two convictions were overturned.

In the meantime, he remains in solitary confinement, living out his days in a 6-foot-by-9-foot cell, punished for a crime he argues he did not commit. There's no telling what 43 years away from other people has done to him, and it's hard to imagine what sort of life he will have if and when he is released back into the world, having been away from it for so long.

There are a few things we know about solitary confinement — none of them good.

In 2011, the United Nations called on countries to do away with solitary confinement. The argument is that the mental abuse prisoners in solitary undergo as the result of their placement can amount to torture.

“Solitary confinement is a harsh measure which is contrary to rehabilitation, the aim of the penitentiary system,” said UN special rapporteur on torture Juan E. Méndez.

"Considering the severe mental pain or suffering solitary confinement may cause," he added, "it can amount to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment when used as a punishment, during pretrial detention, indefinitely or for a prolonged period, for persons with mental disabilities or juveniles."

A detainee makes a call from his "segregation cell" at the Adelanto Detention Facility in Adelanto, Califoria. Photo by John Moore/Getty Images.

We know studies have shown solitary confinement doesn't actually make anyone any safer. In fact, some find that people held in solitary confinement for extended periods of time actually become more likely to become violent.

We know that somewhere around 80,000 prisoners are being held in solitary confinement at any given time.

We know that it costs three times as much to house someone in solitary confinement than in the general population.

No matter how you look at it, keeping people in solitary confinement for extended periods of time simply doesn't make sense.

In July, President Obama ordered the Department of Justice to review the use of solitary confinement in U.S. prisons.

He showed skepticism for the practice, calling it "not smart."

"I’ve asked my attorney general to start a review of the overuse of solitary confinement across American prisons," said Obama during a speech at the NAACP conference. "The social science shows that an environment like that is often more likely to make inmates more alienated, more hostile, potentially more violent. Do we really think it makes sense to lock so many people alone in tiny cells for 23 hours a day, sometimes for months or even years at a time?"

Obama meets with Attorney General Loretta Lynch in the Oval Office on May 29, 2015. Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images.

The review has been completed, and the president is adopting its recommendations.

In an editorial from The Washington Post on Jan. 25, the president outlined exactly what that means:

- Banning solitary confinement for juveniles

- Banning solitary confinement as a punishment for "low-level infractions"

- Reducing the amount of time inmates in solitary must stay in their cells

- Expanding on-site mental health resources

By the president and Department of Justice's estimate, this will affect somewhere around 10,000 inmates.

It's stories like Woodfox's that makes Obama's latest action so huge.

It's rarely "necessary" to hold someone in solitary, and Obama's new guidelines clearly state that inmates should be "housed in the least restrictive setting necessary to ensure their own safety, as well as the safety of staff, other inmates, and the public."

The president's move doesn't go so far as to eliminate the use of solitary confinement, but it does set the framework for future reviews of the system, which could in turn bring an end to the practice.

Baby boomer grandparents.via

Baby boomer grandparents.via  A stressed mom with her head in her hands.via

A stressed mom with her head in her hands.via  A stressed mom doing laundry.via

A stressed mom doing laundry.via  A father does his daughter's hair

A father does his daughter's hair A father plays chess with his daughter

A father plays chess with his daughter A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto

a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

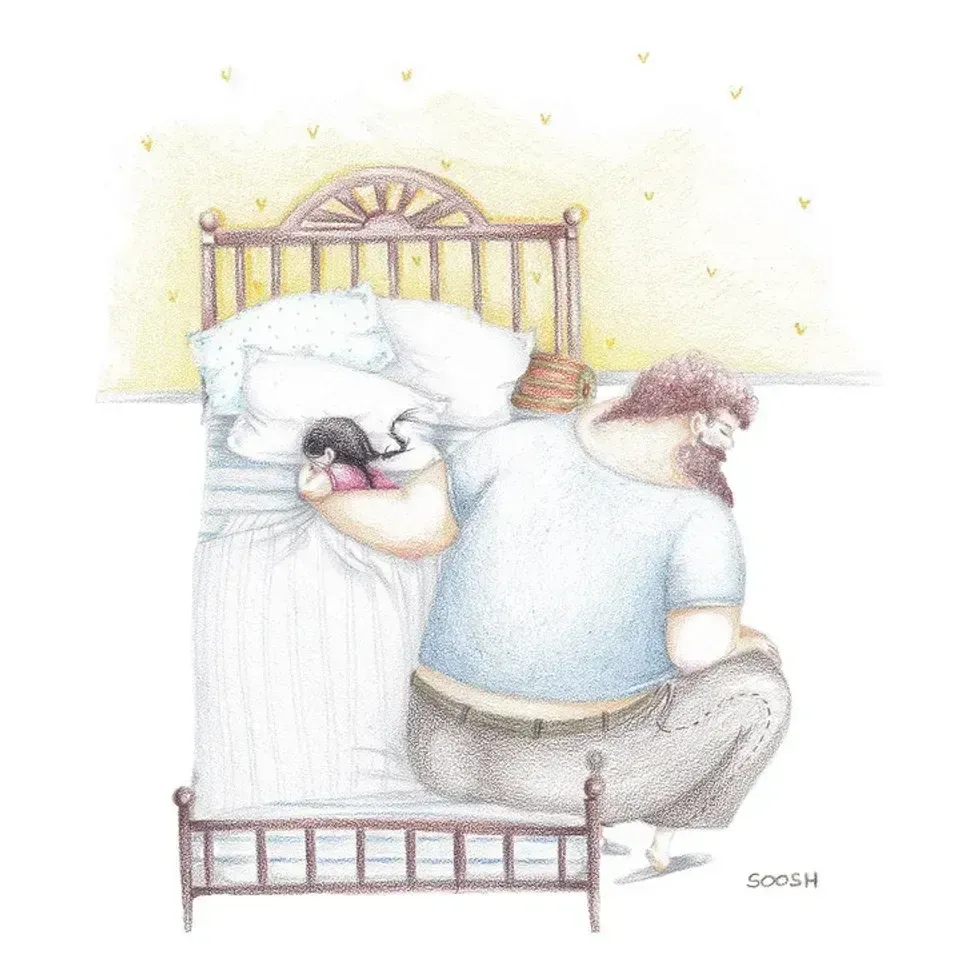

A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

Photo by

Photo by

A 1980s computer and television. via

A 1980s computer and television. via