As a member of the Bloods, Trinidad Ramkissoon never expected to make it to Broadway.

Ramkissoon was the youngest of seven children, and while his immigrant parents worked hard to provide for them, the family still struggled, even enduring a bout of homelessness after their Cambridge, Massachusetts, apartment burned down.

With his father working 16-hour days and his only brother in prison for a violent crime, Ramkissoon was on the lookout for role models — and on the streets of Cambridge, gang life was the best option he could see.

“This was a family connection for me for a long time,” he told the Boston Globe in 2012. “Sometimes I [still] wear [the gang flag] just to own that — to, like, acknowledge it.”

[rebelmouse-image 19345920 dam="1" original_size="640x400" caption="Central Square, Cambridge, near where Ramkissoon grew up. Photo by Tony Webster/Flickr." expand=1]Central Square, Cambridge, near where Ramkissoon grew up. Photo by Tony Webster/Flickr.

By the age of 12, Ramkissoon had already been arrested, which led to a school suspension.

From the start, he wasn't set up for success.

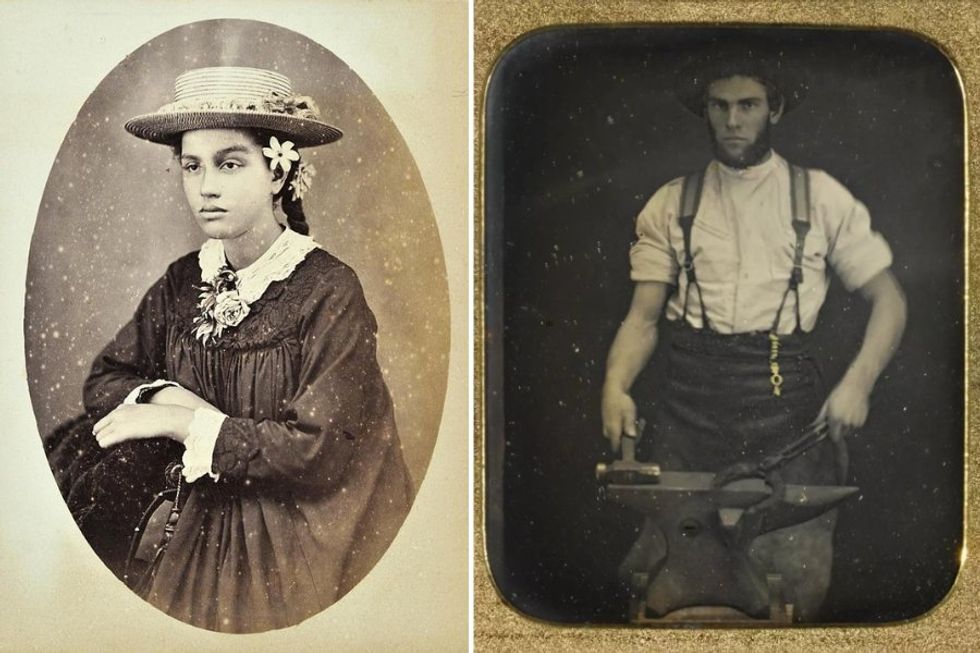

[rebelmouse-image 19345921 dam="1" original_size="1240x769" caption="Trinidad Ramkissoon. Photo via Huntington Theatre Company/YouTube." expand=1]Trinidad Ramkissoon. Photo via Huntington Theatre Company/YouTube.

It comes as no surprise, then, that Ramkissoon would be caught skipping class as a high school freshman. But it was a mistake that would change everything.

He and his friends were reprimanded by Elaine Koury, the director of the arts program at Cambridge Rindge and Latin School, who also worked with a local company called Underground Railway Theater. She was struck by how apologetic — and charismatic — Ramkissoon was and decided to recruit him into a youth theater program.

It was there that Ramkissoon began to learn how to let his guard down.

“It opened something up in me,” he says. “And even more it connected me with Vincent [Siders, one of the teaching artists], who took on a father role with me and started saying what I needed to hear — even when the words have been tough and I haven’t liked what he was saying.”

[rebelmouse-image 19345922 dam="1" original_size="1337x769" caption="Ramkissoon on stage. Photo via Huntington Theatre Company/YouTube." expand=1]Ramkissoon on stage. Photo via Huntington Theatre Company/YouTube.

High school theater programs are known to reduce dropout rates by giving students a shared sense of purpose and responsibility — and a reason to continue attending school.

Theater wouldn't stop Ramkissoon from dropping out at first, but it did help bring him back.

After about a year out of school, he enrolled in Boston Day and Evening Academy, a unique program that helps students re-engage in academics on a personalized education track.

As a student there, he also discovered the plays of August Wilson through a partnership with another local theater company.

[rebelmouse-image 19345923 dam="1" original_size="1024x809" caption="August Wilson. Photo via Huntington Theatre Company/Flickr." expand=1]August Wilson. Photo via Huntington Theatre Company/Flickr.

Wilson was an African-American renowned for “Century Cycle,” a series of 10 interconnected plays that explore the black experience in America, each across a different decade of the 21st century. Ramkissoon was particularly drawn to the character of Troy Maxson in the award-winning play (and now movie) “Fences.”

“I was a high school dropout. I know what it means to feel like you’re on first base,” Ramkissoon said, referring to one of Maxson’s monologues in the play. “I thought it was amazing that [the character] had the courage to want to make it to second base — not to get home, but just to go to second base.”

Ramkissoon got involved in the August Wilson Monologue Competition, a national theater contest organized by Tony Award-winner Kenny Leon.

His performance of Troy Maxson’s moving monologue was good enough to earn him a spot in the national finals — on the set of Leon’s Broadway production of “A Raisin in the Sun,” where he got to perform for people like Denzel Washington.

"For many of our students through the city, being invisible is the way of safety and surviving," said one teacher from Boston Day and Evening Academy. "Yet these young people [like Trinidad] ... find their voices and courageously say, 'see me and hear the truth that I have to tell.'"

“The fact that my voice gets to be heard on this platform… These are all opportunities that kids like us don’t get,” he told the Boston Globe on the eve of the finals. “I already won.”

[rebelmouse-image 19345924 dam="1" original_size="500x509" caption="Trinidad Ramkissoon, in back, on his way to the August Wilson Monologue Competition. Photo via Huntington Theatre Company." expand=1]Trinidad Ramkissoon, in back, on his way to the August Wilson Monologue Competition. Photo via Huntington Theatre Company.

Ramkissoon didn’t end up winning the national competition — but he did get to be the speaker when he graduated high school.

Students like Ramkissoon who come from lower socioeconomic statuses are more than 30% more likely to pursue a bachelor’s degree if they’ve experienced a high-arts education. They’re also twice as likely to choose a major that aligns them with a professional career, even if it’s not related to the theater.

But, perhaps most importantly, a theater education can mean the difference between a life on the streets and a life fulfilled, where talented people like Trinidad Ramkissoon can live up to their potential and become a part of something bigger than themselves.

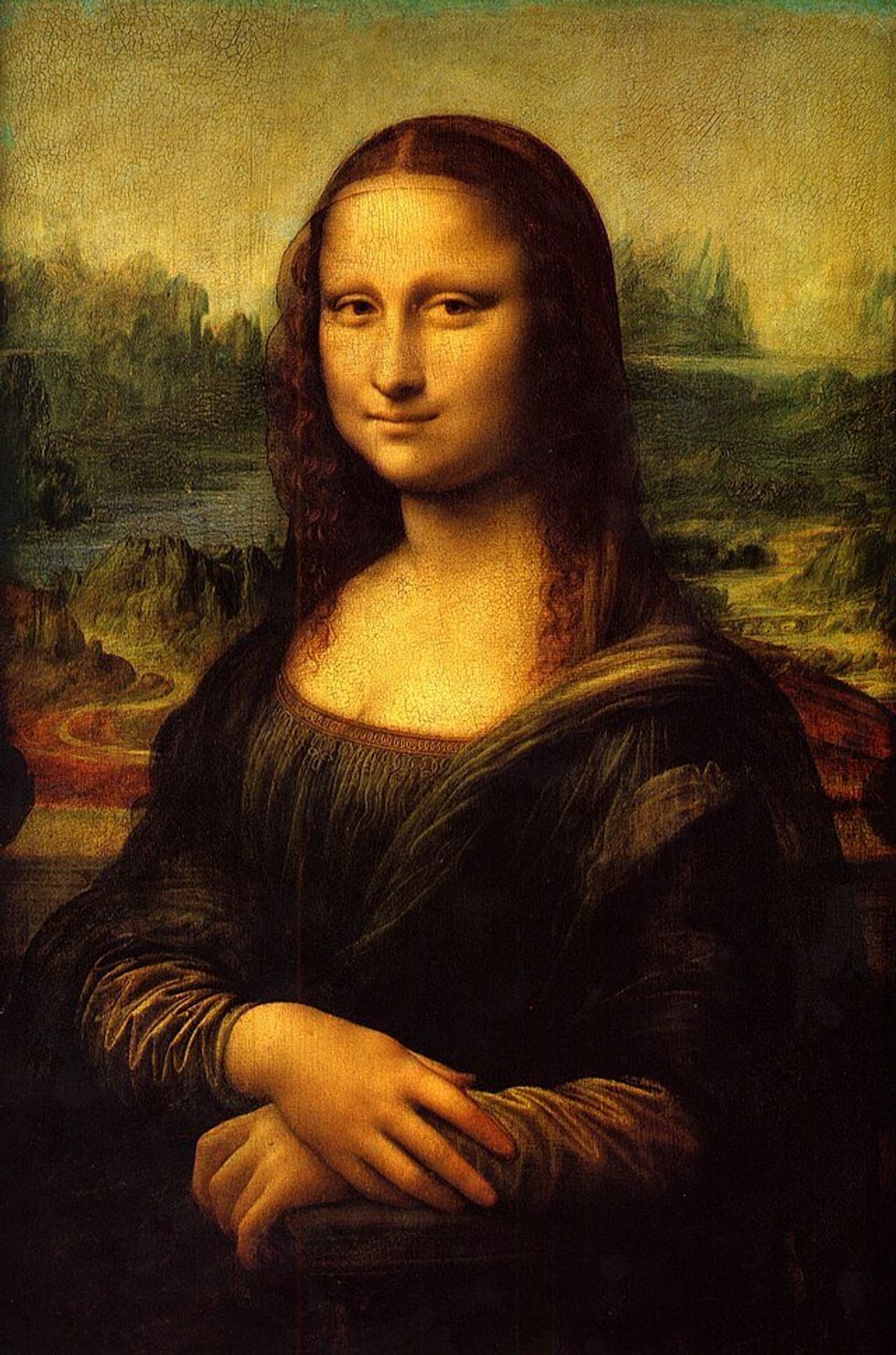

Why so serious? Public domain

Why so serious? Public domain "Mona Lisa" by Leonardo da Vinci, painted in 1503Public domain

"Mona Lisa" by Leonardo da Vinci, painted in 1503Public domain "Malle Babbe" by Frans Hals, sometime between 1640 and 1646Public domain

"Malle Babbe" by Frans Hals, sometime between 1640 and 1646Public domain Even wedding party photos didn't appear to be joyful occasions.

Even wedding party photos didn't appear to be joyful occasions.