He's black. He's a cop. He's also been stopped and frisked 30 times.

He was upset when the police stopped him the first time. But by the 30th time, there was an ironic reason why he was downright embarrassed.

Meet Nick.

Nick was a superstar athlete in high school who still loves to jog regularly. Nice, friendly looking guy, right?

Nick believes in abiding by the law. It's actually a hugely important value to him (you'll understand why later ... keep reading).

So why has he been stopped and frisked by the police 30 times?

"I have been stopped lots of times, sometimes driving my car; other times, I've been stopped on the street. And I've had some really poor experiences. ... It's intimidating when you know you haven't done anything wrong, that it's frustrating. It's also embarrassing." — Nick

Nick was guilty of driving, walking, and, essentially, living while black — an all-too-common narrative that has resulted in people getting stopped and searched everywhere from inside cabs to their own apartment buildings. But that's not where the story ends.

In case you don't know what stop-and-frisk is, it's a highly controversial practice when an officer stops someone who s/he thinks "looks suspicious" and frisks them for weapons. A crime-intervention policy that has sparked national and international debate over its fairness and legality, stop-and-frisk was initiated by the police and still receives tons of support from police.

But here's the irony: Nick, a black man who has been stopped and frisked 30 times, is the police. That's right. Nick is a cop.

BOOM. Imagine that: constantly being a victim of a policy supported and implemented by the same organization that you work for. That cuts pretty deep.

"It makes you wary of a police car behind you or police officers in the street, which seems really weird when I'm a police officer myself. But I genuinely do feel that." — Nick

So Nick is working with Equally Ours in the U.K., speaking up about this problem that he has experienced firsthand from both sides of the issue. And he knows it's a big problem — not just in his own life, but statistically speaking too.

Let's run the numbers.

Research from the New York Civil Liberties Union shows that stop-and-frisk in New York focuses on men of color, which seems totally skewed if you look at the total population.

For example, NYCLU's stats say that in 2011:

- 168,126 young black men (between the ages of 14 and 24) were stopped by the police.

- This makes up 25.6% of NYPD stops.

- Young black men are only 1.9% of the city's population.

- In the same year, only 24,760 young white men were stopped.

- That accounts for 3.8% of NYPD stops.

- Young white men also make up 2% of the city's population.

Between 2003 and 2012, stop-and-frisk climbed by a whopping 600% in New York, but only a small percentage of those incidents involved police finding someone carrying a gun or attempting to commit a violent crime. According to the NYCLU, during that time, stops increased by 524,873, but officers found only 176 more guns.

Granted, any number of guns off the streets helps, but does finding them really have to involve such racially insensitive tactics that affect hundreds of thousands of innocent people?

The good news is that stop-and-frisk practices in New York have started to dip. There's a big difference in the numbers from 2013 to 2014.

- In 2013, New Yorkers were stopped by the police 191,558 times.

169,252 were totally innocent (88 percent).

104,958 were black (56 percent).

55,191 were Latino (29 percent).

20,877 were white (11 percent).

- In 2014, New Yorkers were stopped by the police 46,235 times.

38,051 were totally innocent (82 percent).

24,777 were black (55 percent).

12,662 were Latino (29 percent).

5,536 were white (12 percent).

Most attribute this to a 2013 case New York. U.S. District Judge Shira Scheindlin ruled that stop-and-frisk is "unconstitutional and racially discriminatory." Part of the settlement in this groundbreaking case required that the NYPD put reforms in place, including more intense monitoring and accountability for these incidents, along with requiring that officers wear body cameras.

That sounds like a good place to start, but implementing these reforms has been difficult because of various appeals, negotiations, and, more recently, having Judge Scheindlin removed from the case, which caused some of the reforms to be put on hold.

A father does his daughter's hair

A father does his daughter's hair A father plays chess with his daughter

A father plays chess with his daughter A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto

a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. If you think socks are socks, think again.

If you think socks are socks, think again. You spend a third of your life on a mattress, so you want it to be a good one.

You spend a third of your life on a mattress, so you want it to be a good one. A good quality bra that fits is priceless.

A good quality bra that fits is priceless. Professional movers make moving so much less stressful, physically and mentally.

Professional movers make moving so much less stressful, physically and mentally. Cleaners save time, stress, and sometimes even relationships.

Cleaners save time, stress, and sometimes even relationships. Vet bills can be painful, but are 100% worth it.

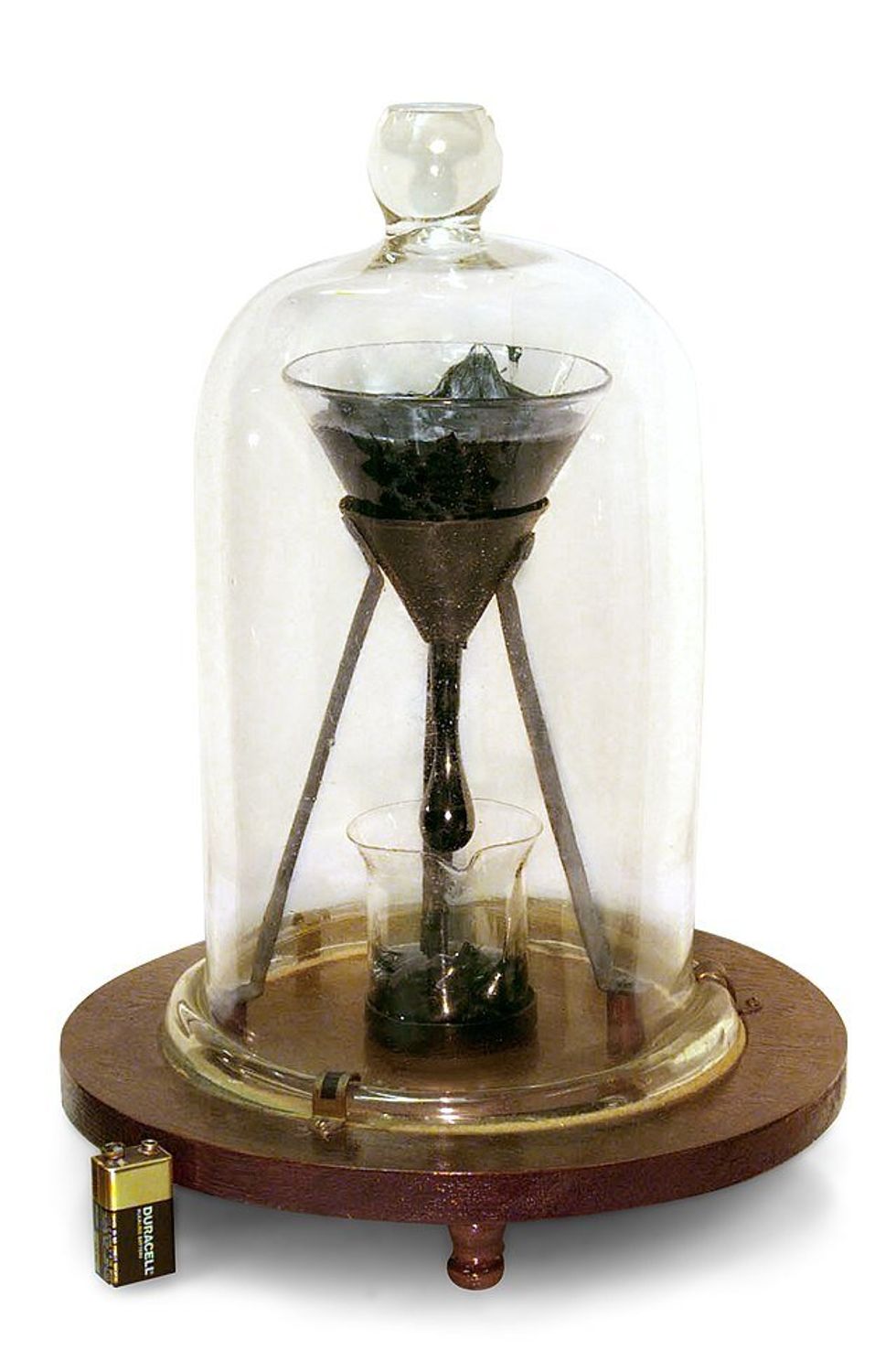

Vet bills can be painful, but are 100% worth it. Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference.

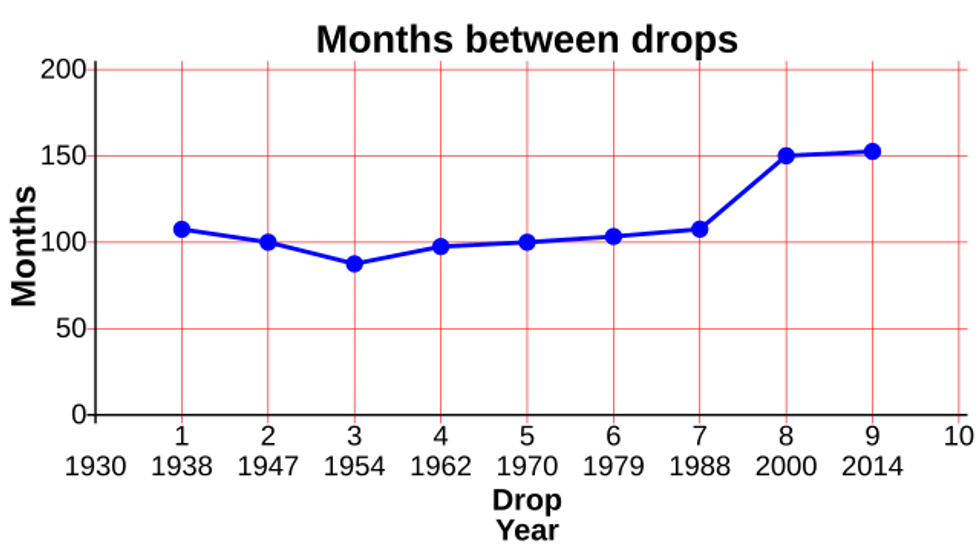

Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference. The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years.

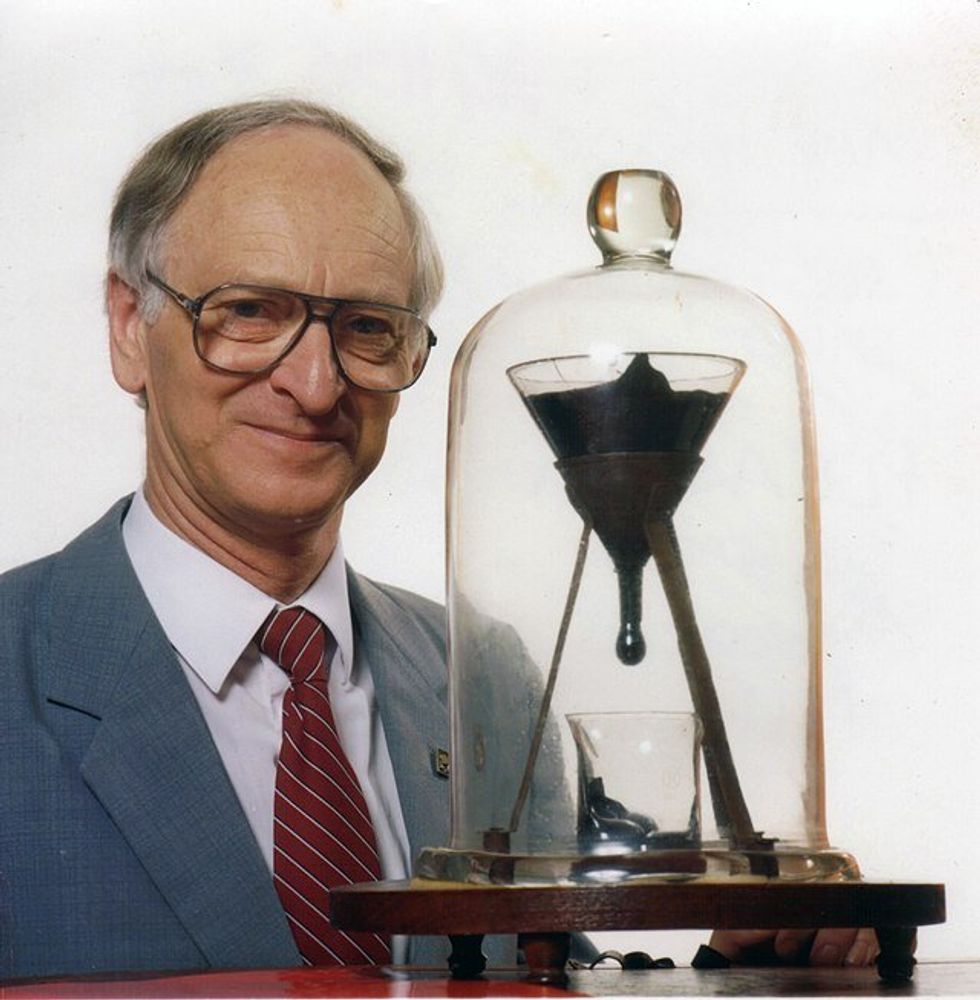

The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years. John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990.

John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990. Happy Music Video GIF by Chrissy Metz

Happy Music Video GIF by Chrissy Metz Many pets on the street belong to unhoused people.

Photo by

Many pets on the street belong to unhoused people.

Photo by