Does cancer follow the rules of math? This scientist certainly thinks so — and she's onto something.

Franziska Michor is quickly becoming a rising star in the worlds of math and medicine and for good reason.

In 2005, at the age of 22, Franziska Michor finished her doctorate in evolutionary biology at Harvard University.

Michor was born in Vienna, Austria, the child of a nurse and a mathematician. Early on, she developed a passion for math that — luckily for humanity — has stuck with her into her adult life.

In a 2007 profile in Esquire magazine, she joked about her father's policy that she and her sister either had to study math or marry a mathematician.

"We said, 'Oh, no, anything but that!' So we studied math."

Photo from The Vilcek Foundation.

While you might think that science, medicine, and math just go together, Michor says that's not the case.

"If you like science but don't like math, you go into medicine," she told Esquire, noting that while the people in medicine might not like math, cancer does.

If we're going to make progress in the fight against cancer, it's going to take math. And that's why her passion for both is so important.

In Vienna, she studied both math and molecular biology, a somewhat unique academic path. With her options limited at home, she moved to the U.S. for her graduate studies.

Since graduating, Michor has become known for her unique, mathematic approach to treatment of one of life's scariest situations: cancer.

Now a professor at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard School of Public Health, Michor incorporates quantitative methods and evolutionary biology in trying to understand what fuels cancer cells.

Photo from The Vilcek Foundation.

As she frames it, "Cancer is the body's fight with rapid evolution within the body."

That is, the human body is in a constant state of change. At any given moment, the body is home to millions (or even billions) of mutated cells. While there's always the possibility that any one of these cells might become cancerous, the overwhelming majority of them are harmless and are eventually destroyed by the body (phew!).

The trouble with treating cancer is that it doesn't exist in a vacuum. There are treatments that can wipe out cancerous cells, but if it's also destroying healthy cells essential to survival, that pretty obviously presents a problem.

In 2015, she received the Vilcek Prize for Creative Promise in Biomedical Science for her work developing new approaches to treating cancer.

So much of her work has centered around optimizing the scheduling and dosages used in drugs for treating cancer. Her approach has found some major success.

Vilcek Prizes are given to "immigrants who have made lasting contributions to American society through their extraordinary achievements in biomedical research and the arts and humanities." Michor certainly fits that category.

From the Vilcek Foundation's website:

"Michor's efforts are driven by the courage to test approaches that defy convention. Her prominence in the United States cancer research community is embodied in the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute-based Physical Science-Oncology Center, a collaborative, interdisciplinary endeavor that she has led since 2009, thanks to a competitive $11 million grant she received from the National Cancer Institute; at the center, researchers apply physical sciences to solve problems in cancer biology. Because the willingness to embrace path-breaking research is embedded deep within the DNA of the American scientific community, says Michor, she finds herself at home in the United States: 'What I love about the United States is that the people are not risk-averse. In Europe, you have to be very convinced that something is going to work before you try it. I am very grateful that I have collaborators who are willing to support me and help test my ideas in the clinic.'"

Her work may save millions of lives, and it's in part the product of her having the opportunity and resources to customize her academic path.

She wants to "teach math to medicine," meaning to take medicine, teach it math, and as a result, create better medicine. Better medicine is always welcome.

Photo from The Vilcek Foundation.

This is a teacher who cares.

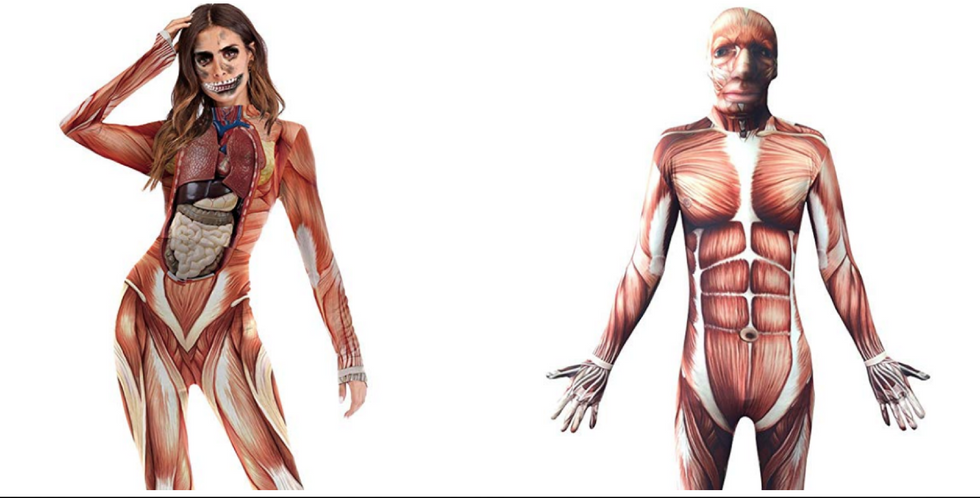

This is a teacher who cares.  Halloween costume, check.

Halloween costume, check.  Wealth Inequality is a rampant problem.

Photo by

Wealth Inequality is a rampant problem.

Photo by  Summer Fall GIF by Mark Rober

Summer Fall GIF by Mark Rober Raining Stick Figure GIF by State Champs

Raining Stick Figure GIF by State Champs Where we started.

Where we started. Paradise in the backyard

Paradise in the backyard Welcome to Whelan Design House.

Welcome to Whelan Design House. Beauty is possible!

Beauty is possible! Dads are gonna be dads.

Dads are gonna be dads.