A scientist who has studied polar bears for 34 years is starting to get really worried.

Even after half a lifetime studying polar bears in some of Earth's least hospitable climates, Andrew Derocher still gets nervous trying to tag a 1,000-pound bear on a frozen slab of ice in the open water.

"[The bears] are not worried about being out there, but it’s just not good enough for us," he says.

Photo by Andrew Derocher.

To human researchers, sea ice may be a rickety death trap, but to polar bears, it's a little like a cross between a superhighway, a forest, and an old memory-foam mattress. It's the surface over which they travel, where they hunt, and occasionally, where they mate.

And increasingly, Derocher warns, there is less of it to go around:

"We can quibble amongst ourselves as scientists, but the overwhelming scientific consensus is absolutely clear: Polar bears are in trouble."

The ice that supports polar bear populations from Canada to Alaska to Russia to Norway is disappearing — rapidly.

Across the Arctic, the trouble signs are difficult to miss. The bears are getting smaller, they're reproducing less frequently, and very young and very old bears are dying at higher rates.

For the past two weeks, Derocher has been tweeting a series of alarming maps and images that illustrate what polar bears are up against.

Like this one that shows in dark red how much sea ice is missing:

And this one that shows the decline of sea ice coverage:

And this one that shows the decreasing number of days with sea ice per year:

Derocher and his colleagues at the University of Alberta use satellite radios to track the bears' movements.

Since the early 1980s, Derocher has studied thousands of bears over thousands of miles. Some of the bears he tracks today are the great-great-grandchildren of the bears he began his career working with.

By monitoring when the bears walk onto the ice and when they return to shore, they can estimate the number of "ice-free" days the bears will see that year. 180 "ice-free" days is considered a danger zone for the species.

"Once we get beyond about 210 days, we probably no longer have sufficient ice to maintain a viable population," Derocher explains.

In Canada's Western Hudson Bay, the no-ice period is hovering around 150-160 days — but, thanks to climate change, that number is jumping up by an average of three to six weeks per decade.

A few extra weeks without access to the ice can mean the difference between life and death for animals that burn up to two pounds of energy every day they're on land.

Less sea ice means the bears have to travel more, which means they have to kill more seals while they can. Since most of their hunting is done on the ice, that window becomes shorter the later the seas freeze — creating a conundrum wherein the bears have less time in which they're forced to hunt more efficiently and productively.

Derocher working on the ice. Photo by Andrew Derocher.

If they fail to hunt enough, their body fat stores won't last the length of the ice-free season. With lower body fat stored, female bears stop producing milk earlier, leading to higher cub mortality.

Derocher's prognosis for the arctic ambassador species is dire.

Within the next few decades, he estimates, there will be significantly fewer polar bears. By the end of the 21st century, there may be such a reduction in the species' range that future populations may or may not be viable.

"Every time we look at a new study, there’s pretty much no good news for polar bears," he says.

With current planetary warming trends, Derocher fears the decline is not reversible in the short term.

Long term, saving the species might mean making some sacrifices — financial, political, or otherwise.

"In our own house, we had to replace some windows, and we opted to pay the extra money for triple pane to save on energy," he says.

Any U.S. push to return to coal, he fears, would be a disaster for the species, although he does see some cause for optimism in recent business efforts to combat climate change.

Ultimately, he believes, polar bear fans simply need to understand what's going on if the species is going to continue surviving against heavy odds.

Photo by Andrew Derocher.

"There’s nothing in the scientific literature that supports anything but grave concern," he says.

The first step toward getting the bears back on track, he maintains, is getting the public to care about conserving sea ice.

The second is people "voting with their wallet" and rewarding companies that are reducing their carbon footprint.

The third is supporting politicians like those in his home province of Alberta who favor policies like higher carbon taxes — though he believes most could be doing much more.

That might be the species' best hope.

"It’s got to change," Derocher insists. "The way we live on this planet has got to change."

The first deposit of orange peels in 1996.

The first deposit of orange peels in 1996. The site of the orange peel deposit (L) and adjacent pastureland (R).

The site of the orange peel deposit (L) and adjacent pastureland (R). Lab technician Erik Schilling explores the newly overgrown orange peel plot.

Lab technician Erik Schilling explores the newly overgrown orange peel plot. The site after a deposit of orange peels in 1998.

The site after a deposit of orange peels in 1998. The sign after clearing away the vines.

The sign after clearing away the vines. Nobody spoke to goth kids like My Chemical Romance

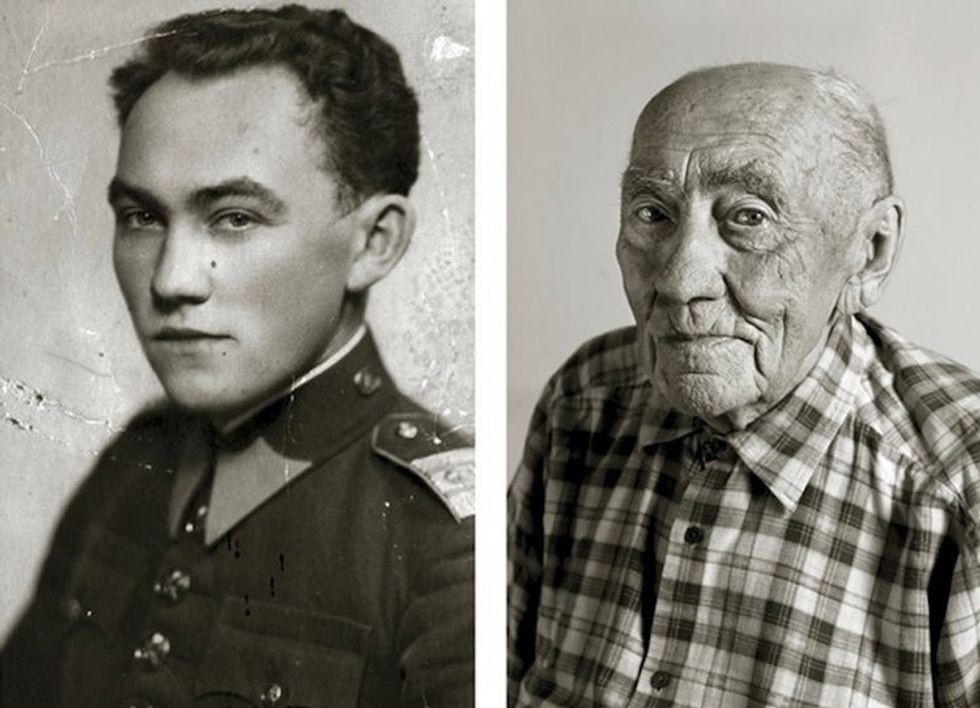

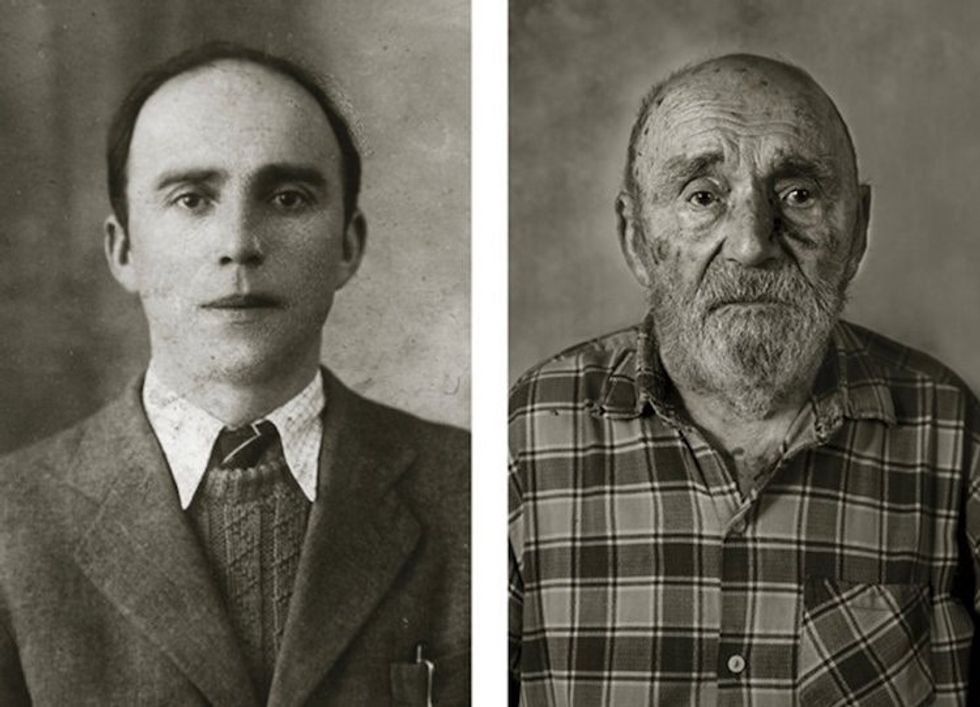

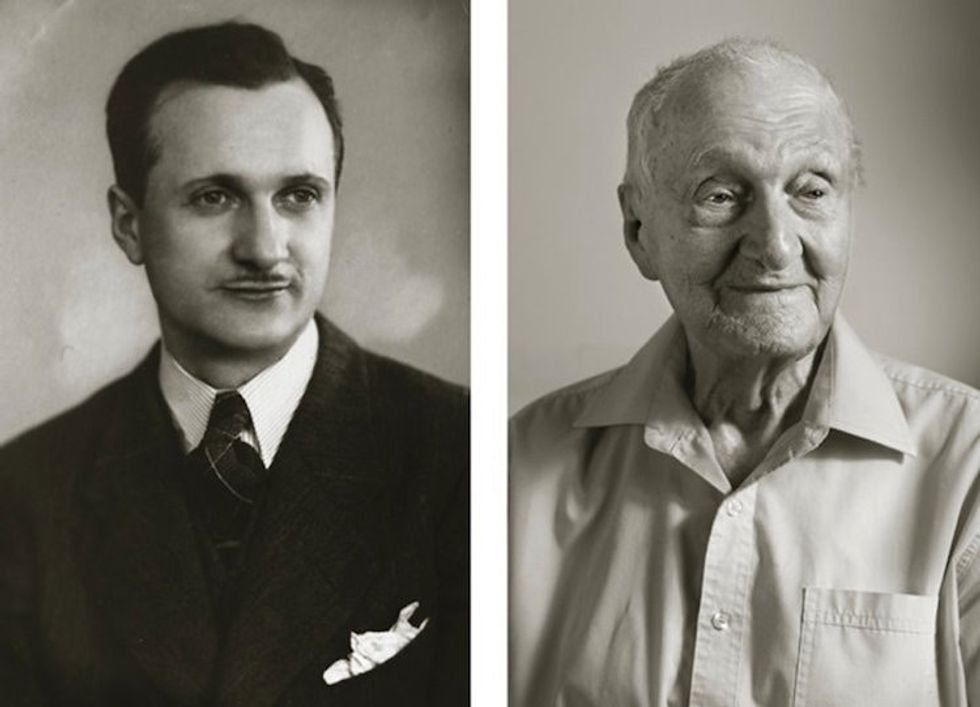

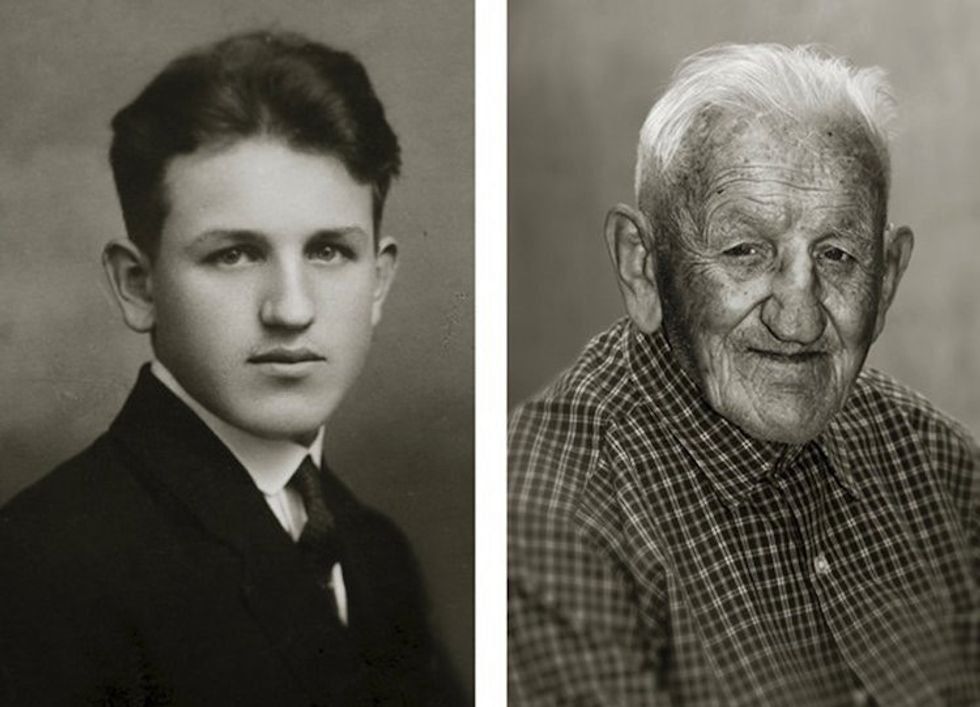

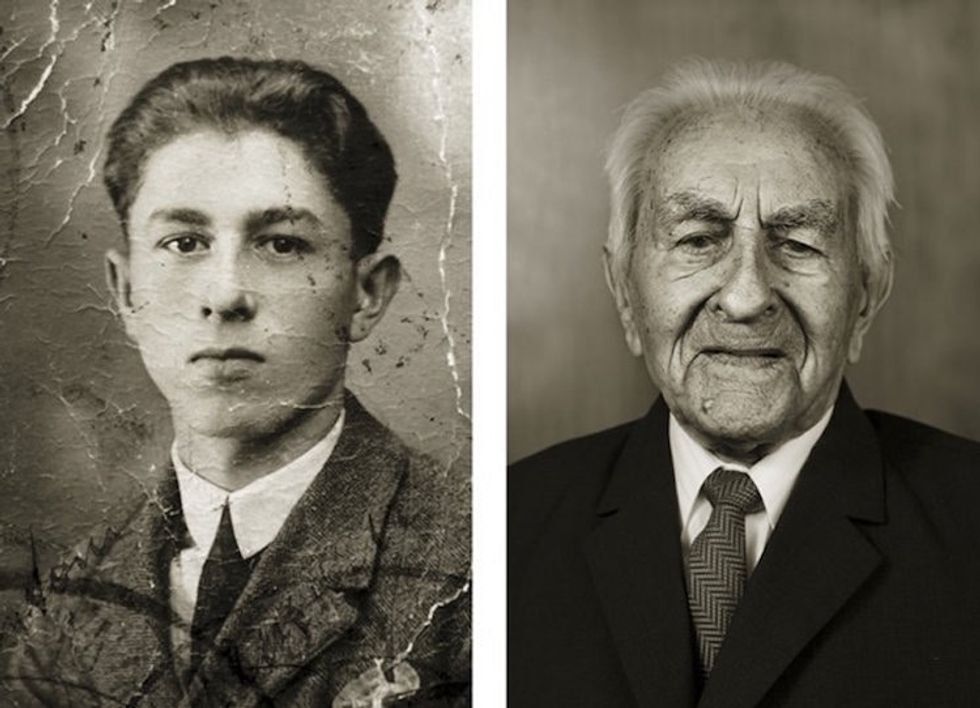

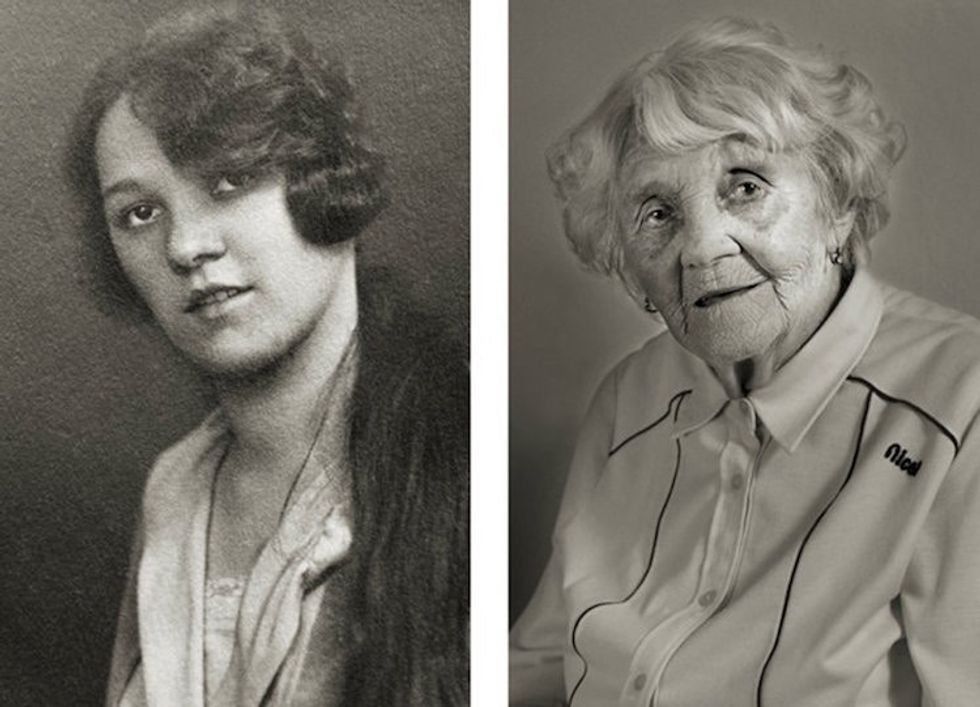

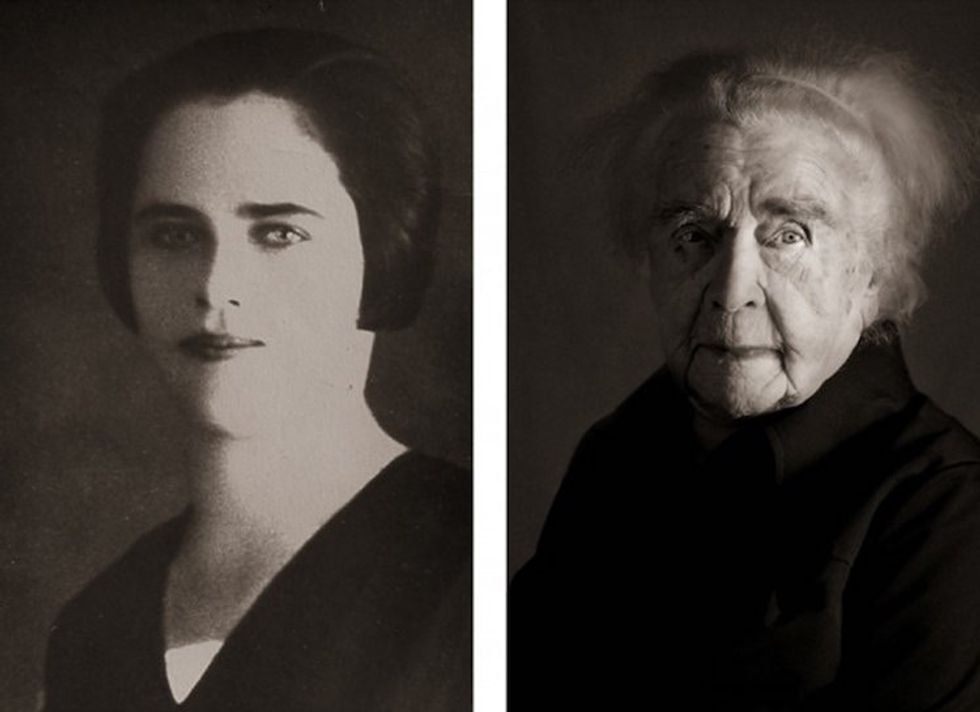

Nobody spoke to goth kids like My Chemical Romance Prokop Vejdělek, at age 22 and 101

Prokop Vejdělek, at age 22 and 101

salutes jack black GIF

salutes jack black GIF jack black happy dance GIF

jack black happy dance GIF I Love You Lol GIF by Lifetime

I Love You Lol GIF by Lifetime A masterclass is classy dating.Via Reddit

A masterclass is classy dating.Via Reddit A little respect goes a long way.Image via Canva

A little respect goes a long way.Image via Canva