No one wants to see the sexual abuse of children occur.

As a result, in most cultures, pedophilia — sexual attraction to children — carries tremendous stigma. This stigma often drives pedophiles underground, and out of sight.

But does that work to keep children safe?

Is there a better way?

A group in Germany has been running a provocative ad campaign with an unusual target: pedophiles.

A Project Dunkelfeld PSA, which translates to: "Do you love kids more than you would like to? There is help. Free and confidential." Photo by Project Dunkelfeld.

The campaign is sponsored by Prevention Project Dunkelfeld (the "dark field" project), an organization that provides confidential, free therapy to people who struggle with pedophilia to try to ensure they never act on their impulses.

This includes teaching general self-control, basic situation avoidance — how to effectively steer clear of potentially dangerous, one-on-one interactions with children — and integrating patients into more robust social networks in order to marginalize the importance of sexual desire in patients' daily lives.

The program revolves around a crucial distinction:

"Child molestation and pedophilia are not synonymous."

Image by Project Dunkelfeld.

According to Fred Berlin, director of the National Institute for the Study, Prevention and Treatment of Sexual Trauma (a private treatment center in Baltimore), "virtuous pedophiles," or people who are sexually attracted to children but have never abused and never intend to abuse a child, are out there. And right now, in the United States, they're not getting help.

"I think we have to encourage people who are undetected to come forward so that we can assist them before they cross the line," Berlin said.

“We have to get beyond this idea that sex offenders are monsters and recognize that they are among us, and that they can be helped," says Elizabeth LeTourneau, director of the Moore Center for the Prevention of Child Sexual Abuse at Johns Hopkins University.

LeTourneau told Upworthy that after "This American Life" featured her Maryland center in a report, she received over 200 inquiries from people who struggle with sexual attraction to children and claim to have never abused a child.

They reached out to her for help despite America's mandatory reporting laws.

These laws require health professionals in most U.S. states to notify authorities if they suspect one of their patients is a danger to children.

LeTourneau supports those laws but believes states should take a more nuanced approach.

"Many, many people who are attracted to children do not want to hurt children, and people who have already done so really want to stop," she said. She says it's important to "give them a way to access services where they don't also have to face the decision to risk 15 years in prison."

Germany's lack of mandatory reporting laws allows Project Dunkelfeld's therapists to provide judgment-free support at no legal risk to participants.

This Project Dunkelfeld PSA includes a phone number to call for help. Image by Project Dunkelfeld.

Strict laws in Germany prevent therapists from breaking confidentiality with their patients, though they can provide information to the authorities if a patient makes it clear they intend to commit a serious crime. No such laws exist in the U.S., although therapists are still ethically bound to confidentiality except in cases of danger and must comply with HIPAA.

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of the program is that therapists even help people who have abused children or consumed child pornography in the past.

Image by Project Dunkelfeld.

According to a report by Damien McGuinness of the BBC, this even includes abusers whose crimes have never been reported.

Q: So what does a therapist do if a patient says he has abused a child?

"If he comes to us and says, 'I have done something illegal in the past and don't want to do it again,' and that's the normal case for us, then we can help him to build up his self-regulatory behaviour to not do that again," says clinical psychologist and sexologist Anna Konrad of the Charite hospital in Berlin.

Q: But surely, I suggest, it's difficult to sit opposite a man who has abused children and try to help him?

"The main aim of the project is to protect children from being abused, and if I can help the person not to do that again, then for me it's quite clear that I should do that," she says.

The Project Dunkelfeld website features testimonials from patients who credit the program with teaching them how to manage their desires and live normal lives.

Christian, a civil servant, writes:

Jan, another patient, writes:

The accounts can be difficult, even shocking to read. But it makes you wonder:

Could a program like this work in the United States? Would communities here accept it?

Image by Project Dunkelfeld.

“There are well-validated prevention programs of every conceivable type of childhood violence except for childhood sexual abuse, and that's because we've convinced ourselves that the people that commit these crimes are monsters," LeTourneau said. "They can't be stopped. They can't be helped. They're monsters, and all we can do is wait for them to do their horrible thing and then send them away for 10, 20, or 100 years. And that's ridiculous."

Right now, laws in most states make an aggressive prevention approach like Project Dunkelfeld difficult, if not impossible, to implement in the U.S.

Though the BBC reports that over 5,000 people have reached out to the German program for help and advice since it launched in 2005 and that over 400 men have begun treatment, how effective it's actually been at reducing incidences of child sexual abuse remains to be studied.

But despite how repulsive their desires might seem, people who are sexually attracted to children are not demons — they're people.

They're already in our communities, our churches, our schools, and yes, sometimes our homes.

Mandatory reporting laws might not have to go away, but perhaps they can be modified to allow those who don't want to abuse to come out of the shadows and seek help from trained specialists. It would require making some tough choices, but it could lead to fewer tragic outcomes and fewer children hurt.

Pedophiles need help. The question is: Are we willing to do what it takes to help them?

This is a teacher who cares.

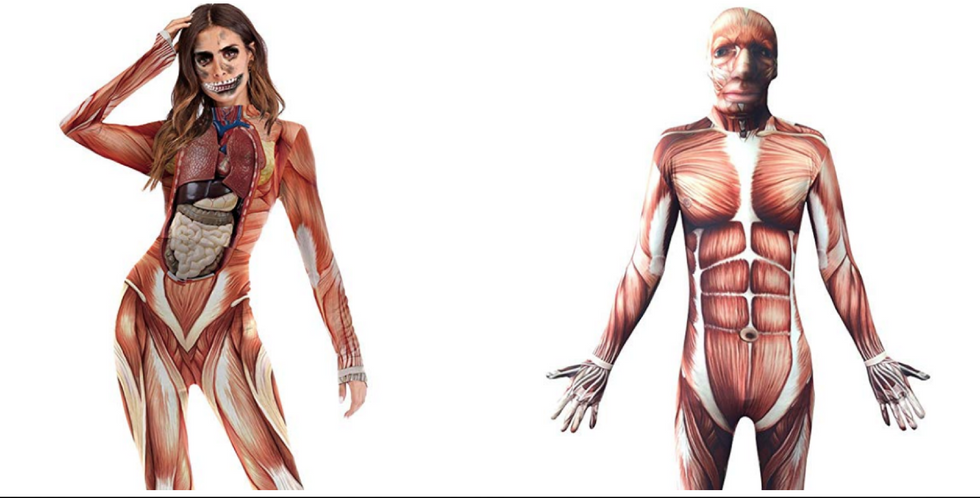

This is a teacher who cares.  Halloween costume, check.

Halloween costume, check.  Don Draper from AMC's "Mad Men" Image via "Mad Men" AMC

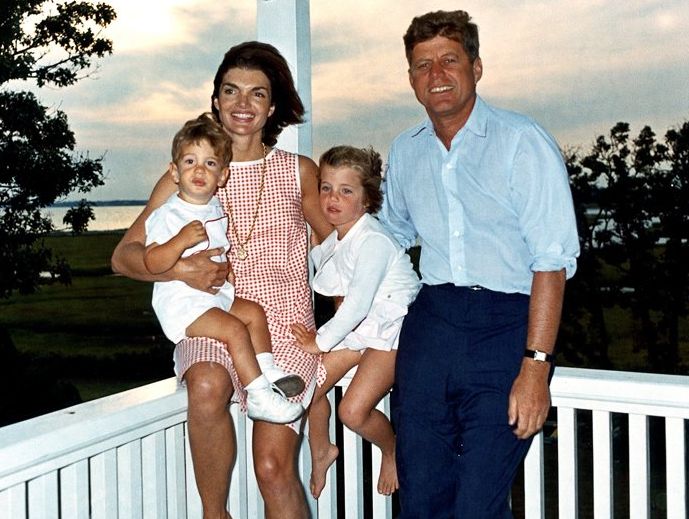

Don Draper from AMC's "Mad Men" Image via "Mad Men" AMC John F. Kennedy with his family Image via Wikicommons

John F. Kennedy with his family Image via Wikicommons An adorable French Bulldogvia

An adorable French Bulldogvia  french bulldog gifofdogs GIF by Rover.com

french bulldog gifofdogs GIF by Rover.com A grown woman and her motherImage via Canva

A grown woman and her motherImage via Canva An adult woman and her older motherImage via Canva

An adult woman and her older motherImage via Canva