The video begins with a man in a blue and orange coat surrounded by strangers breaking down on a Greek beach.

For a moment, he sobs, clutching his daughter — no more than six years old — tightly to his chest. A person from the crowd drapes a thin, grey blanket around him. Then, suddenly, he begins to panic. He holds up a few fingers — first four, then two.

He is a refugee, and his first moments on European soil were captured on tape by Rory Aurora Richards, a Canadian volunteer working to aid the thousands of men, women, and children landing in Greece after fleeing persecution in their home countries.

"He was from one of about 13 boats we brought in that night. Scenes like this are not uncommon," Richards told Upworthy.

"People come off the boats very traumatized. The relief of being on safe land triggers a deep release of emotion and trauma."

Richards is one of dozens of volunteers from around the world who have traveled to Lesbos Island in Greece to aid refugees fleeing war in Syria and around the Middle East.

Though neighboring Turkey is often the first stop for many refugees from Syria and the Middle East, many ultimately decide to attempt to continue on to Europe. When refugees successfully complete the dangerous, over-water crossing, Lesbos is often where they land.

Roughly 6,000 refugees arrive on the island per day, according to some estimates.

Lifeguards rescue refugees from a boat off a Lesbos beach. Photo by Rory Aurora Richards/Facebook, used with permission.

According to Richards, who is raising money for the relief efforts on Lesbos, the volunteers operate individually or in separate groups organized by country of origin.

While the volunteer teams only occasionally coordinate, they share a common goal: giving aid and comfort to people in great danger.

"The only thing that binds us together is compassion and the concern for human lives," Richards says of her fellow volunteers.

It was this compassion, as well as a sense of duty drawn from own religious and cultural background, that led Richards to offer her services at her own expense.

"I'm Jewish, so the reality of genocide and being a refugee resonates deeply for me," she says.

Richards praised the dedication and compassion of her fellow volunteers, many of whom frequently risk their lives to save the incoming refugees.

"The Spanish lifeguards, as a group, are incredibly impressive. They physically go out into the cold water and retrieve the boats," Richards said. "They work 24/7, and I have seen them put themselves in extreme danger many times. They are all volunteers. I hope people in Spain know who they are and what they do."

Lifeguards from Spain, waiting on the arrival of a refugee boat. Photo by Rory Aurora Richards/Facebook, used with permission.

Richards also singled out a group of Israeli doctors and medics who spend their nights treating the wounded and the sick upon arrival.

Wars around the Middle East have displaced millions of people just like the man that Richards filmed on the beach.

The civil war in Syria has already displaced and uprooted over 4 million people.

Caught between Bashar al-Assad's army and ISIS, nearly a quarter of the population of that country has fled rather than stay and risk death, imprisonment, or worse. While the trip across the Mediterranean might be less hazardous, it is only barely so. Over 3,400 people have died making the crossing in 2015 alone.

Refugees wait to cross near the Greek border. Photo by Milos Bicanski/Getty Images.

Even after making the trecherous journey, many refugees have had trouble finding a home in Europe. While Germany prepares to accept over 800,000 refugees this year, thousands more remain in refugee camps throughout the continent, prevented from crossing national borders.

"If you had a family, and children ... wouldn't you want to take them to a place where they would be most safe, and that they had the most of amount of opportunities? This is human instinct ... . Why is that shameful?"

Meanwhile, the decision to take in 10,000 Syrian refugees has ignited a political firestorm in the United States, over fears that violent extremists might be among the resettled. More than half of all state governors have declared that refugees from Syria are not welcome in their states, despite the fact that they don't actually have the power to refuse refugees.

As someone who's met dozens of refugee families, and witnessed their suffering up close, Richards says she finds this attitude frustrating and difficult to understand.

A refugee couple Richards met in Lesbos. According to Richards, they fled war in Afghanistan and arrived via a treacherous trip through Iran and Turkey. Photo by Rory Aurora Richards/Facebook, used with permission.

"They are human, with same emotions and dreams as we have," Richards said. "People say, 'Oh, well, of course they want to go to Western Europe, or the USA or Canada ... they all want to go the richest countries. Well, wouldn't you too? If you had a family, and children ... wouldn't you want to take them to a place where they would be most safe and that they had the most of amount of opportunities? This is human instinct that we all have for our children. Why is that shameful?"

As for the man in the blue and orange coat, Richards and the volunteer team were, thankfully, able to help him.

Photo by Rory Aurora Richards/Facebook, used with permission.

"Doctors went him immediately and asked him if he was injured, and then an interpreter said he was not physically hurt, he was just scared," Richards explained. "His children were being treated nearby but he lost sight of them and began to panic ... . [But] we found his children immediately and reunited them."

For the volunteers, the rescue was all in a day's work.

"You don't have too much time to process," Richards said. "The lifeguard came over to tell us that another boat was near shore and was taking on water.

"We had to flee this crisis scene to attend to another."

Many people make bucket lists of things they want in life.

Many people make bucket lists of things they want in life.

sipping modern family GIF

sipping modern family GIF

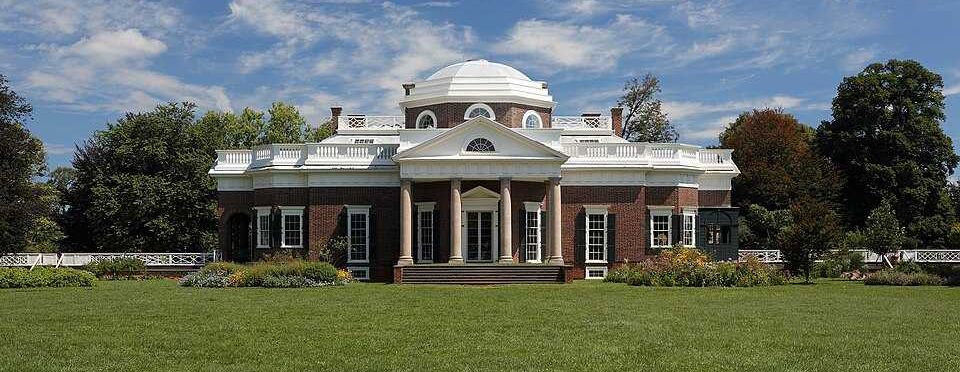

Thomas Jefferson's Monticello.via

Thomas Jefferson's Monticello.via  The Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C.via Joe Ravi/Wikimedia Commons

The Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C.via Joe Ravi/Wikimedia Commons

The 1992 Olympics were held in Barcelona. Photo by

The 1992 Olympics were held in Barcelona. Photo by